Kaiako Highlight: Jim Critchley

- Lian Soh

- Aug 28, 2025

- 5 min read

Jim Critchley has spent over two decades trying to inspire his students at Mount Maunganui College to love Science. He is currently the Teacher-in-Charge of Earth and Space Science at his kura and serves as a regional representative for the Earth and Space Science Educators Association of New Zealand (ESSENZ). Earlier this year, Jim also helped with the AI Business Summit, raising funds to support scholarships for overseas learning trips.

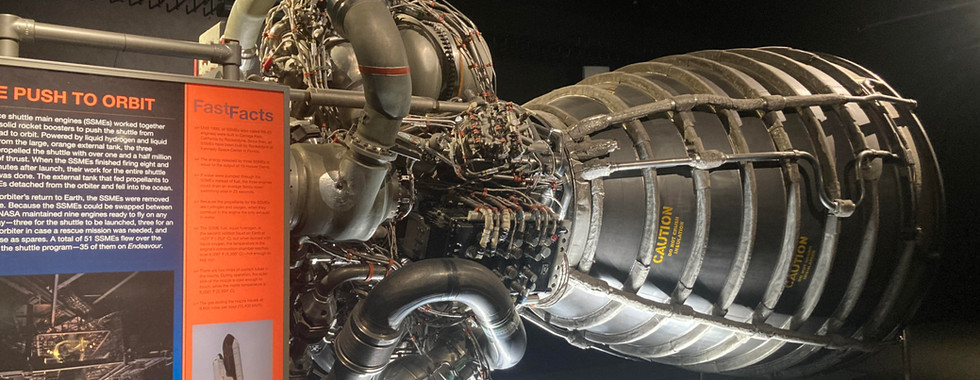

Whether it’s planning astronomy trips to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab and telescopes in Hawai‘i, building partnerships with industry for environmental and technological projects, or guiding student groups to tackle Anthropocene challenges through systems thinking, Jim believes learning and engagement are strengthened when students can connect theory with real life. Nowhere is this clearer than in Earth and Space Science

Earth and Space Science brings together physics, geology, astronomy, and environmental science in ways that make the ‘why’ of science tangible. Images supplied; © Jim Critchley.

Jim’s own story — leaving school at 16 with only a pass in PE theory at GCSE, finding his footing in the Air Force, and later stumbling across a university prospectus that drew him into sport science — underpins his philosophy that every student deserves the chance to find their spark, no matter how long it takes. For Jim, it was a chance encounter that changed the course of his life. In the classroom, he works to create as many of those moments as possible, opening doors through new opportunities, field trips, and guest speakers so his students can discover their own spark.

It all comes down to engagement — what are we going to do to engage students? That’s everything, isn’t it? There’s no silver bullet, but we can’t keep doing what we’ve always done. We have to keep evolving, keeping up with as much of the latest Science as possible, engagement is key.

Beyond his own classroom, Jim is a strong advocate for keeping science education future-focused, relevant and inclusive. He often speaks about the urgency of engaging students in ways that matter, and on topics which are becoming increasingly urgent for rangatahi such as climate change, sustainability and the opportunities offered by new technologies.

To understand more about what drives Jim's approach to science teaching, we asked him a few questions about his journey through science and schooling.

1) What did you enjoy about science at school — and why?

Honestly, I didn’t enjoy science at school at all. I went to three different secondary schools, and with all that moving around I never really felt a connection anywhere. I just wanted to play football — schoolwork wasn’t my priority. Science didn’t excite me, and I certainly didn’t see myself as a science person back then.

The only subject I managed to pass was PE theory. That gave me one GCSE when I left school at 16. Looking back, I realise it wasn’t that I couldn’t learn — I just hadn’t found something that clicked. So no, science wasn’t something I loved at school; in fact, it was the opposite. My real passion for science only emerged much later in life.

Jim has also helped to organise and set up a seismometer and meteor camera at Mount Maunganui College. Images supplied; © Jim Critchley.

2) What led you to consider science education as a career path?

After failing school, I joined the Air Force and served for six and a half years. It gave me structure, but while travelling through Scandinavia during my service I began to realise there was more to life. One turning point came when I was staying with a friend — his sister had a couple of university prospectuses lying around. I picked them up and thought, "Sport science actually sounds really interesting".

Jim knows a single moment can change a life. He creates those moments for students by finding opportunities, trips, and guest speakers. Images supplied; © Jim Critchley.

I applied and was lucky enough to get in. An officer in the RAF, who I played squash with, helped me write my covering letter — and that definitely made the difference. There’s no doubt that letter got me through! At first, my science knowledge was terrible, and I had to put in hours and hours of extra work at home to catch up.

But what kept me going was discovering that science could be relevant. Through sport science, I saw how biology, chemistry, and physics connected to something I cared about — sport. That’s when it really hooked me.

That journey shaped how I teach. If I could leave school at 16 with one GCSE, then end up becoming a science teacher, who am I to tell any student they can’t do it? Sometimes it just takes longer. Some kids might be 23, like I was, before they’re ready. My role is to make sure the door is still open for them when that moment comes.

3) What do you see as key learning experiences for students in science?

It all comes down to engagement. Students need to know why science matters. Trips, guest speakers, hands-on experiences — those are what stay with them. I’ve taken students to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, to see telescopes in Hawai‘i, to talk with engineers who never went to university but are working on world-class projects. You never know which moment will spark something in a student.

I try to use real-life contexts to answer their biggest question: ‘Why do I need to know this?’ If they get the why, they’re motivated. That’s true whether it’s physics, Earth and space science, or climate change. I use analogies — if one person saves one kg of carbon dioxide, it doesn't make a difference. If everyone in New Zealand saves one kg of carbon dioxide, then it makes a massive difference. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. That helps them see the power of collective action.

Science education needs to show the interconnectedness of systems — environment, climate, economy, society. Indigenous cultures have always known this. If we can help students see those connections, then science isn’t just about content, it’s about shaping how they understand the world and their place in it.

That’s the challenge and the opportunity. We can’t keep doing what we’ve always done, we have to keep evolving, keeping up with as much of the latest Science as possible, engagement is key. The real task for us as kaiako is to create those moments of connection — where science feels meaningful, urgent, and human. When students see that, they start to believe they can make a difference. And that, in the end, is everything.

Earth and Space Science opens doors to explore how technology and science have evolved — a vital skill for navigating misinformation in today’s information-rich world. Images supplied; © Jim Critchley.

Ngā mihi nui ki a koe, Jim, for sharing your journey and passion for Earth and Space Science. Your mahi continues to open doors for rangatahi, sparking curiosity and creating opportunities that connect science with the real world. Thank you also for your ongoing contributions to our region, and for sharing news with Bay Science. |

Comments